Into The Groove

Why do a lot of us audiophiles (and casual listener types) prefer the sound of records over the same music released digitally? Is it something about the inferiority of digital? Are vinyl records, without those sacrilegious anti-aliasing filters and stair-step samples, somehow higher in resolution? Or is it simply the much-heralded warmth of vinyl?

Some would say digital is superior without the surface noise, side length limitations, and inner groove distortion. So what’s the point of putting digital mixes on an analog record? Records should be cut from an analog master, right? I’m not talking about the ritual of owning and playing records. Putting aside the factors of having a tangible object that requires more care and intention, along with the fun of combing bins for used treasures and everything else that goes with being a record collector, let’s explore the sonics and what’s responsible for that warm and fuzzy feeling we often get when having a platter party.

Words and Photos by Dave McNair

Everyone hears things differently. Folks have different tastes for what lights up that pleasure center in our brains. It’s a subject I talk about a lot with my audiophile friends, especially the record lovers. So I figured during these times of new-found popularity and interest in vinyl I might as well use my experiences to pour some more gasoline on the fire. I’m not trying to convince anyone, just some food for thought aimed at the curious readers out there, digital fans included.

First off I want to dispel the notion that vinyl is somehow a higher resolution format, as alleged by some—especially in the early days of bad sounding CDs. It was sometimes stated (and still is) that a record contains more information from the source material than a digital release does. Nope. While I can’t scientifically prove it, the experiences from my job as a mastering engineer who also cuts lacquers for vinyl production, tells me this is not so. Not counting poorly done, hyped eq, overly peak limited remasters that frequently are done without the artist’s approval, the digital release is a stone-cold faithful version of what the artist and production team intended the listener to hear.

This or that DAC or 44.1K vs. 192K is like asking which shape snowflake do you prefer when the artist simply wants us to see the snow on the mountain as they intended us to see it. Debating DACs or some exotic digital playback tweaks is fine, but just about any old DAC will give you what the artist wanted.

But if we listen to that same music on a good-to-great vinyl playback system it seems like things sound very different and I would argue more compelling. More real and substantive. Some kind of hard to describe lifelike quality that is subtle but somehow makes for a deeper listening experience. What’s going on here?

Searching For My Lost Shaker Of Iron Oxide

Digital got a bad reputation among audiophiles from the beginning, and rightly so—yet this was not the experience of most music fans in those early days. My first generation Sony CD player in many ways sounded better than the budget turntable setup I was using at the time. It had a punch, tightness, clarity, and lack of noise that I had only heard in the studio. And we were under the impression that the discs were indestructible with no ability to wear out like a vinyl record. Yeah, right. It was also brittle, congested, and dry sounding. I didn’t listen at home with an audiophile sensibility in those days so it wasn’t immediately apparent to me that the early CDs and players were like a sponge that someone used to wring out all the subtle yet enjoyable qualities to the music. Right down the perfect sound forever drain.

Meanwhile, in the studio, I was using 24 track analog tape for most projects but started doing some jazz sessions which I recorded live, to 2 track digital. We proudly used a new Sony PCM-F1 system that recorded 16-bit 44.1 or 48K to either VHS or Beta videotape. All of us were flabbergasted with how great it sounded. I had for some years been a little bummed out with how even well-regarded professional multi-track tape machines sounded, which was easily audible on playback immediately after having just heard the feed from the console as the musicians performed live. By the way, those 24 track decks all sound different, but that’s another discussion.

So now with the Sony PCM-F1, we had a way to perfectly capture the feed from the microphones, without any noise, softening of transients, change in the feel of the bottom end, or smearing of high-frequency energy like vocal sibilance and cymbals. There was also a period for me, and a lot of other engineers, where most of my projects were recorded to analog multi-track and then mixed down through an analog console to an early stereo digital recording machine (ADAT or Alesis Masterlink). I thought it sounded way better than our analog tape, quarter-inch head, 30 inches per second, stereo mixdown deck. Going back to that all-machines-sound-different thing, maybe if we had had an Ampex ATR-102 half-inch at that studio, we wouldn’t have preferred the Sony digital…

That love affair proved to be short-lived for me when digital multi-track machines appeared on the scene. I used most of them. Mitsubishi X-800, X-850, X-80, X-86, Sony 3324, 3348, 1610, 1630, Sony DAT machines, Panasonic DAT machines, you name it. While some were not horrible, I couldn’t shake the feeling of something being off. The worst was the Alesis ADAT format followed in close second by early versions of ProTools. I used to say those sounded like plastic cardboard. Then there was the time my assistant during an all-digital mix session exclaimed dryly “Dave, it sounds like the cat just threw up a digital hairball.”

Strangely enough, most 2 channel DAT machines sounded fine to me.

In the HiFi world, manufacturers were trying to figure out how to make those shiny discs sound good, or at least better. I credit most of the developments in converter design to the Objectivists of the HiFi world. It might have looked amazing on paper to the techies but the experienced listeners screamed bloody murder and the designers implemented improvements—not only to home digital playback but also a trickle-down to the pro audio, digital recording world.

Today, using good converters, I feel like professional digital recording systems (including ProTools) have finally matured and, in fact, sound about as good as they ever need to. They are essentially colorless. Completely faithful to the source. Isn’t that what HiFi is all about? But wait, don’t a lot of digital recordings still sound shitty? Why yes, yes they do. But some don’t. Some sound amazing. Warm, wide, clear, harmonically rich.

What’s happening there?

We are now at the point where the engineer is no longer fighting an inferior, lower resolution, recording medium. Recording and mixing engineers have discovered that the best way to make digitally recorded music sound engaging is to introduce layers of various distortions to give our brains a hit of what naturally happens from analog tape and lots of trips through an analog console. With the almost universal acceptance of digital audio workstations, most engineers I know stay completely digital once it gets into the computer. No tape. No going through an analog console. There is a real art to making this sound great. I know one engineer who refers to his process as one of “sonic varnish.” He likes to use digital processing to create small amounts of different distortions and in various layers to arrive at the most pleasing sound. He’s not alone.

In the old days, using top-shelf pro analog gear, and if you had decent ears and employed best practices during your recording, that analog sound that everybody loves and talks about (and many engineers now seek to emulate) was simply baked in—an inherent part of the process when using those tools. Which is missing when using digital tools, especially in the mixing phase. Hence the popularity of digital plugins that seek to emulate the sound of analog gear’s distortions and non-linearity.

Can I Get That Platter With A Side Order Of Fries?

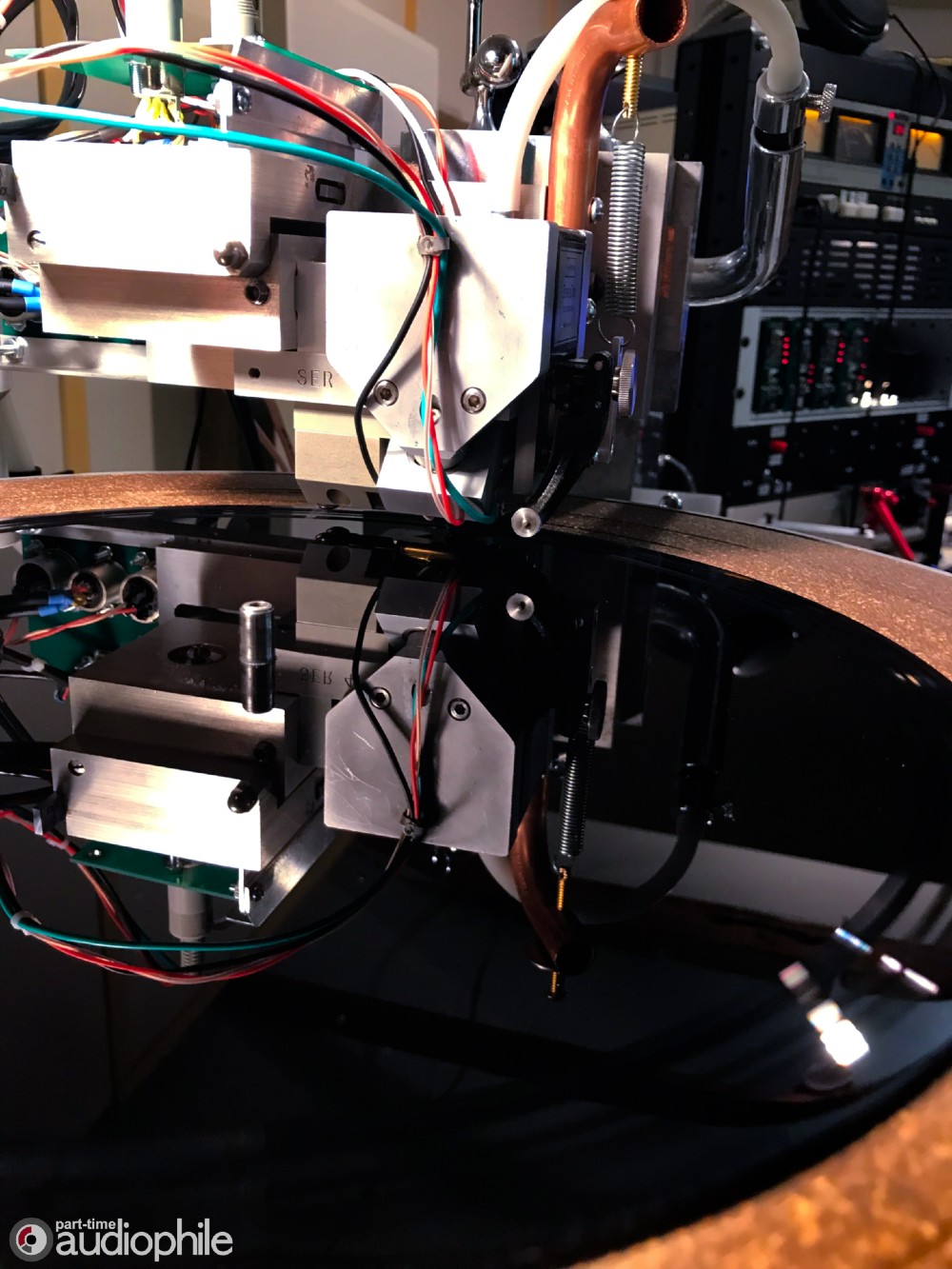

Cutting a lacquer and directly comparing it to the source master is fascinating and illuminating in several ways. One thing I’ve learned is brands and models of lathes sound different from each other. This has a direct impact on the sound of the finished record. In my particular setup, (custom Scully with Westrex cutter head and hybrid tube and solid-state electronics), the lacquer almost always sounds better overall than what I send to it to be cut. Think about it. The electronics have a sound, the head has a sound, and to some degree, the mechanical parts of the lathe have a sound. I won’t even get into the additional colorations of the playback chain—you get the idea.

All of this is separate from whatever the engineer did (if anything) to manipulate the signal to get a good cut. My cutting system has a fair degree of sonic color but I love its sound. It’s true enough to the source program material but with a paradoxically slight smoothing effect in the upper mid and a great sense of punch and dynamic contrast. Also, there’s a little more vivid mid-range with some added air on top. While not as wide sounding as the source (cutter heads and cartridges might have 25db of separation on a good day), there is some kind of intangible sonic mojo that makes imaging quality seem more palpable. Similar to the typical vacuum tube gear in a HiFi playback system, the tubes in the front end of my cutting rack give the low end a largeness or bloom which I generally like. I’m also having a solid-state front end version finalized that I can use on stuff that needs to sound tighter down there. Other lathes I’ve heard and compared can sound tighter, more damped, maybe more refined but also lacking the exciting dynamics and luscious mid-range of my system.

Getting all these attributes to transfer to a final record after the lacquer goes to electroplating and pressing is a major ordeal. Crazy making. When the right folks are part of this production chain the results can be amazing.

I’ll Just Play Records Until I Need Glasses

So it should turn out to be no surprise that for a digital master mix, one more layer of analog colorations from a cutting system can be just what the doctor ordered. At least to my ear. Certainly, a well done all-analog recording can also sound great on vinyl. Some might consider an all-analog cut to be the pinnacle of the art form. I certainly do. But if you want to hear an analog final mix or a digitally produced recording sound as close to how it was intended to be heard, listen on good digital. I usually prefer the additional coloration of the vinyl process even if the source was analog, but that’s just my preference.

I think part of it is the added noise. Not pops and clicks, but something different. Even on a record with a very minimal amount of surface noise, there is noise. It’s uncorrelated stereo noise primarily from the heated cutter head stylus dragging through virgin nitro-cellulose. A little of that gives our brain the psycho-acoustic cues we interpret as things sounding wider and deeper. I know this, cause I’ve added stereo tape hiss in very low levels to digital mixes and you wouldn’t believe what good things it does to the sound!

There is another element to my argument that involves what source the lacquers are cut from. It’s not a universal thing but is becoming increasingly more common for the lacquers to be cut from less limited or even non-peak limited files—bonus points if the non-limited master is native sample rate and bit depth. By native, I mean a higher resolution mix before 16-bit, 44.1K conversion for Red Book CD spec. The amount of limiting done by the mastering engineer to get the final mix up to the desired (sometimes ridiculous) level demanded by many artists has no relevance in the vinyl world and can even make it more difficult to cut. This is another reason why records can seem more dynamic and alive sounding than the same release heard on CD or streamed. However, I have heard records that I perceived as more engaging than the CD even though I knew the record was cut from the loud, limited 16-bit 44.1K digital release.

Yes, poor digital can suck the life out of a signal. And poor analog, especially tape, can rob the signal of a lot of great things as well. Can the marriage of well done current digital music production when transferred to a record sound great? You betcha! I will, however, admit that there are a lot of bad sounding records out there to the extent that the digital release can easily sound better. But when reissues of older titles (and new music) are done with care by sound-oriented labels or by independent artists who are in control of the process, and not initially in huge quantities like a typical ’70s major label release, it’s not as likely the buyer will get something stamped on cheap or recycled PVC and from worn-out stampers.

I truly consider the vinyl resurgence to be a golden age of sound for record and music lovers. Okay, give me a minute to put on my flame retardant suit then let me know what y’all think in the comment section below.

More articles from The Ivory Tower

- How Recordings Are Produced, and What It Means to Your Hi-Fi

- Hi-Fi: Why Do Records Sound Better?

- Hi-Fi: How Do We Listen?

- Hi-Fi: What Does It Sound Like?

- The Loudness Wars

About the author, Dave McNair

Dave McNair has been a professional recording engineer, mixer, producer, audiophile, and for the last 20 years, a multiple Grammy-winning mastering engineer. Since his earliest days, music has been a constant. Starting with seeing The Beatles live on Ed Sullivan to studying classical guitar from age 11, then later a series of rock bands, his love of music, sound, and tech, lead him to a career in music recording. Concurrent to beginning his engineering career, he sold high-end home audio in several locations including Innovative Audio and Sound By Singer in NYC. After years of residence in NYC, Los Angeles, and Austin, he now resides in Winston-Salem, NC where he operates Dave McNair Mastering and spends his free time listening to records, reading, meditating, cooking vegan food, hiking, riding road bikes and swapping out hi-fi gear in search of a better sound.

Very interesting article. Thanks. This is the first time I hear somebody saying that the lacquer cutting process could make the sound more pleasing. I have always found the master tape better when compared to the final LP. I have not listened to the lacquer itself as I do not have access to it, only test pressings. On the other hand, my tape playback (Nagra T Audio with custom tube electronics) is better than my LP playback (Classic Turntable Company 301, tweaked SME 3012 with Ikeda 9TT). I like the bit about going through an analogue console or even a tape machine to add analogue distortion to digital recordings. I wonder if the more preferable analogue sound is due to the fact that the rest of the hi-fi playback chain was developed during the analogue era at a time when LP playback was king, and therefore optimised to make analogue recordings sound their best ? Has anyone actually redesigned electronics and especially speakers with a view to improving digital playback ?

I just received a copy of W. Keith Campbell’s new book, “The New Science of Narcissism.”

I purchased it in an attempt to better understand its personal application, cultural relevance and to (possibly) help me cope as November 3rd nears.

While I’m not sure what “New Science” yet refers to, I have considered the scientific method as a method of inquiry requiring little need for change. Rather, our questions and response to these questions have become more refined with respect to the tools we have developed for measuring stuff and identifying variables within the context of an objective causal order–and from a theoretical approach, the space between stuff.

As a species, we have become skilled toolmakers, even if the tools keep us in a feedback loop where questions often become begged for their own sake, in service to a paradigm, ad infinitum.

In the field of psychology, “sensation and perception” could well serve as an example of humans developing tools to test and measure concepts of “being in the world” or the banal presupposition of a mind-body junction point (e.g., Descartes’ perspective on the pineal gland).

Still, the evidence-based approach to how we experience the world (e.g., hear recorded music), while a fascinating area of study, it “wrests” within a paradox: the mind seeking to understand the mind–with or without tools.

This does not mean all hope is lost when it comes learning, at least with respect to making better recording and playback gear, and developing our “ear,” which may require a modicum of self-examination when it comes to identifying what we like and understanding more about why we like what we like, irrespective of measurements.

I mean, could you imagine not liking a peer reviewed “scientifically documented” vanilla ice cream, proven to be superior to your mom’s homemade recipe.

Talk about pressure: I’m either stupid for rejecting the science based recipe, or suffer insurmountable guilt and shame for rejecting mom’s.

And then there’s “technology.”

In a recent motorcycle test of a 2020 Ducati vs. a 2005 Suzuki, the 15 year-old Suzuki was deemed the overall winner, even if the Ducati was preferred for its beauty.

And while advancements in material science have been significant and beneficial in many industries, I have surprised myself with a general preference for paper cones and textile dome tweeters to produce overall better sound than, e.g., more sophisticated ceramics and ribbons.

What can be measured quantitatively does not always equate to a qualitative experience, albeit I would like to know a loudspeaker’s impedance curve and phase angles before placing it in a system.

As a world in search of advancement, where what can be quantified often serves as the metric, and advancement is often mistaken for a yearning to better understand our potential as human beings, I find it refreshing to read about people’s qualitative description of hearing/listening to recorded music–no matter the medium, all the while trying to understand and control functional variables.

Thank you, Mr. McNair.

A mixed bag we are, in search of ourselves, often in places offering little reward.

After reading the introduction to the “new science” book, unless a richer, more qualitative relationship focused approach is discussed, I’m afraid the lean toward an evidence-based cognitive-behavioral model could leave me feeling a bit empty.

It must be those primordial, preverbal urges to ‘say something’ coming through again.

It must be time to vote. . .

Steven, it seems like we may be kindred souls in the quest for a better understanding of how our minds process sensory input while listening to music on our systems. I look forward to hearing your speakers and continuing the discussion with you.

wonder how you would compare Rudy Van Gelder’s recorded sound to Roy Dunann’s?

Why Do Records Sound Better? Well to my ears, given the digital formats I listen to, they don’t. Yes, poorly recorded, mixed and mastered MP3s and redbook CDs, etc. can sound terrible. Same is true for tape and vinyl. But quality recorded, mixed and mastered PCM 96-192kHz, DXD and high resolution DSD64-DSD512 music files sound far superior to my ears and are far more convenient and long lasting.

Like a comment above, I have wondered if the RIAA EQ curve has something to do with the favorable reaction to vinyl records. I did not see that addressed directly in your article. Could you comment on that?

The RIAA curve is not a sonic thing. It’s simply to get more level on the record and reduce surface noise. How accurately and using what kind of circuitry the phono pre amplifies a mirror image of the record eq curve is only one part of the equation.

I used to have that digital/analog war going on between my ears. I grew up on analog and I heard the early digital as a step in the wrong direction. Now that digital has matured and come into its own, and even a lot of well produced vinyl is available, I have to say that my best CDs are better than most of my vinyl and my best vinyl is better than most of my CDs. Now I enjoy them both. Great article.

Very well said. I couldn’t agree more!

Back in the day, I made hundreds of mix tapes (R2R and cassette) with LPs as the source. The technique I used to minimize the space between cuts was to listen through headphones for the “pre-play” of the intro of the LP track, and hit “record” just before the “real” track began. I assumed that the ability to hear the “beginning before the beginning” (pre-echo?) might be caused by the stylus picking up tiny undulations from the immediately following groove. I then wondered if that subtle yet clearly audible phenomenon continued through the entire record, thus possibly applying a form of (often complimentary) harmonic distortion, or if signal-to-noise effects made them effectively inaudible once the “real” track began. Can you finally clear this up for me? Thank you!

Bruce, you are correct. The pre-echo is caused by the upcoming groove shape modulating a previous unmodulated (silent) groove. I have heard from very knowledgeable cutters that this is caused or likely exaggerated when the plating of a lacquer occurs. The metal plating will microscopically expand to push a hint of the groove shape into the adjacent grooves. This really only happens when there is very little land between the groove and a very loud passage is next to silence or a very quiet passage AND the cutting engineer wasn’t on top of things enough to manually “add land” during the cut to put more distance between adjacent grooves. I can’t comment on what effect or what the audibility of this is during the music. As a side note, I doubt this happens on a DMM cut because of the stiffness of a copper blank as opposed to the far softer property of a lacquer. While not a universal truth, most people slightly prefer the sound of records pressed from parts made from a lacquer rather than Direct Metal Mastering (DMM).

As an audiophile who was always swapping and changing record decks, arms and cartridges in the 80s, I can confidently confirm that CDs now produce a far greater undistorted level of sound than I ever managed to achieve with vinyl. It was an absolute pain having to align the cartridge exactly right in order to obtain the least amount of tracking distortion, which increased audibly as the cartridge reached the inner tracks. On high fidelity cuttings that had a high dynamic range, tracking distortion was audible on loud transients in the music if you listened closely enough and could even cause the cartridge to jump on very loud transients. CD was supposed to be an audiophiles dream but early technology was pretty woeful and produced an even worse sound than vinyl, Bruce Springsteen’s The River being a typical example. However that was nearly 40 years ago during which time the technology now produces some of the best audio you could wish for, and without having to spend hours and hours setting up the record deck, which caused you to listen to listen for imperfections in the sound rather than just relax and enjoy the music, not to mention the very high cost involved. The dynamic range is now far greater than could be achieved with vinyl and you only have to listen to something like Paul Simon’s Graceland to hear that. The sound quality on that album is superb and you don’t need to spend a fortune to hear it. Let the Earth Society bang on as much as they like about vinyl, as far as I’m concerned it’s a marketing ploy in order to boost the flagging sales of audio equipment. High Quality CD is NOW an audiophiles dream while vinyl remains a distant nightmare, and long may it be so.

If you can’t afford a high quality vinyl kit, you can always achieve that pleasing warm distortion with a bottle of scotch

Thanks Dave you clarify why I hate vinyl but I cannot stop buying it! My situation is the top of irony, I bought a turntable to record digitally some albums that I wanted to hear in its pre loudness war era. Now in despite owning a Sonos amp, that in fact converts the turntable output into digital before playing it back to analog, my LPs stack is growing faster than the Hard Drive music unit. All that in despite having access to CD quality streaming. I thought I was going slightly mad!

Hello to a fellow North Carolinian! I found your article informative, though I must confess to still preferring digital. I like crisp precision when I am listening to music and do not yearn for analog warmth, however it might be achieved. Some of this is from being a child of the seventies and hating the imperfections always found on records. With that said, I really enjoy SACDs, which are said to capture some of that analog sound. Again, it was good to hear your perspective without a dismissive my opinion is the only correct one attitude.

Dave, I’ve been a vinyl junkie forever. Literally the bulk of my collection was purchased in the early 90s, at garage sales, when folks were dumping them for CDs (I own about a thousand of those, too, in boxes in the basement.)

It’s not just the sound profile or the media itself. You introduce color into it via the cartridge. Mat. Preamp loading and capacitance. The table itself. You can tailor the sound to highlight what you truly want, which changes the sound, sure. But… It’s like comparing the McIntosh amps in my main system to the Bryston ones in the basement. Speaker choice is another: JBLs in the basement, Canton upstairs, huge difference in style.

Flavor, so to speak, lives everywhere in HiFi.

I’ve spent years building a solid collection, and years finding the table I wanted to maximize it. Personally? Digital has a place. On a plane, traveling, in my car, on my wireless earbuds while outside. All fine.

I literally haven’t had a CD/DVD-A player in a system for about a decade. I don’t miss it. All my digital stuff is ripped to Squeezebox server. It’s great background noise for the Squeezebox Players around the house, but never, ever for critical listening.

Amazing lathe. I’ve always wanted to play with one. Absolutely one of the coolest things…

Sting International

And through the years, I thought it was just me! Great article.

Just to throw a thought out there. With digital, does it have any bearing on the subject that the faster you sample, the closer you get to analogue, but you’ll never, in theory, get there?

The sampling rate for accurately capturing even the tiniest squiggle of information is the one that maps at least 2 samples for the highest frequency. In theory, 44.1K should be sufficient and to my ear is usually fine. Having more data points of a higher sampling rate doesn’t yield more information but allows for other parts of the decoding process (in the DAC) to be manipulated for a sometimes more subjectively pleasing result. Sample rates above 44.1K are not about capturing more info, generally speaking.

Personally i can’t stand the sound of vinyl. I do love analog consoles, tubes, analog synths, even tape, I love the warmth analog brings. I mix in a hybrid style through an analog console into uad hardware with analog preamp emulations as well as tape simulators. I usually even run vst instruments through this process to tame the spiky highs and warm up the sound with transformers. I get why analog sounds more exciting and full and glued together, and yet records always sound noisy and inferior and the serface noise is an absolute deal breaker, not to mention that the medium destroys itself in the act of performing what is was designed to do. That’s bad engineering. I think the true love is vinyl IS the experience! It’s a better experience because you approach it with intention. You stop doing everything else and you listen with intent. When most people put on a record they are ready to love it. Just like people who go to a comedy club are ready to laugh. You have psyched yourself up to enjoy the heck out of this tangible thing. The experience of listen to a record is better because you go about it with purpose. For a myriad of technical reasons it does not sound objectively better, however intent may lead to much more enjoyable experience, just the way food and wine taste better in vacation. Because you make it so with your intention and commitment to the experience.

I totally get it. Many music production people feel the same. I was very much of that mind in times past. It wasn’t until I upgraded my entire record playback chain that I fully embraced the sound. Even now, certain things will sound better in digital form.

As you state, the ritual element in all it’s forms (searching the bins, collecting, holding a thing that is art, different versions, cleaning, etc) is a big part of that psychologically predisposed to like it, thang.

As noted, folks ‘hearing’ is different….as is their vision. Just look at how different the color set up on their HDTV vary from person to person.

I began buying vinyl when I was 5 years old….am 68 now, and have every 45 and LP I bought. I took care of them and they sound good to great today, depending upon the normal wear.

I used to scream at the tv ad where Dick Clark spoke of how great CDs sounded…while vinyl has pops and snaps and scratches. Anyone having vinyl knows the importance of a clean surface without fingerprints or dirt….being careful not to scratch it….and a good stylus, not a worn out one, means an enjoyable listening experience.

I have CDs for use in my car but enjoy my vinyl collection in my house.

How about setting up some double blind listening tests to cut through what could just be inaccurate, subjective observations?

That’s a great idea! But how will a double-blind ABX be evaluated other than our inaccurate, subjective listening?

Fantastic article, Dave. More please!

Thanks, Vance.

I thought CDs would sound as good or better than 1/2 speed master disc. I was really disappointed. It may have to do with production technique. So much of the new recorded material has limited dynamic range. There is an obsession with producers to make CDs sound like bad FM broadcasts.

When I was working as a recording engineer in the 1970s it was normal practise to roll off the bass below 50Hz and add a slight boost at 200Hz.

This ensured the stylus would not bounce off the groove in loud bass passages and the boost was to make it less seem less thin from the roll off. Added warmth.

This was done at the cutting lathe. The two track masters were untouched.

When the same masters were used to create CDs they thus sounded thin, and “inferior”.

There is no reason to believe this practise does not continue.

Therein a fake myth was born.

In addition while a DAC is virtually linear from 5Hz to 200kHz, a vinyl cartridge is never that, subject to all sorts of colouration from the cartridge, the RIAA equaliser used, the phone preamp, etc.

So comparing a coloured, “warmed” vinyl sound to that of it’s digital counterpart is deceitful and inaccurate.

I don’t doubt that was done by some as you observed however, my present-day experience doesn’t see this much. The very low bass is not what is a problem to cut and playback, it’s the 100hz-300hz that is hard to cut and track mainly if it occurs as strongly stereo. Sometimes that area has to be trimmed a bit to get the material to playback without throwing the needle out of the groove. Myself and others I know will filter a bit of stuff below 60hz or so but that is because cutting heads tend to have a boost down there as do many cartridges – so a little bit of low filtering will make the final record sound more like the low end of the source files. If a record compared to the same material on digital sounds very warm in the midbass, that’s usually because your cartridge/turntable is not super accurate in that area. My cart is very warm sounding partially because of a boost in that area – and I like it!

Thank you for a terrific article! Your explanations have cleared up a puzzle I’ve had since a friend and I recorded a not-so-great sounding CD to reel-to-reel and we were both convinced the recording sounded better than the CD.

I wonder if there would be a market for a device that could be inserted between source and amplifier to intentionally add distortion (adjustable for amount and type of distortion) to the signal if it is needed to make the CD listenable.

Thanks again for one of the best articles I’ve read in a long time.

Thanks, Rob. There might be a market for a ‘vinylizer’ but the process that imbues a record with the sound we associate with vinyl is massively complex. Especially taking into account playback non-linearities. I don’t know how feasible it would be although it’s an interesting idea!

Answer: They don’t.

Thanks for your in-depth analysis and conclusion.

The vinyl resurgence is the best thing that ever happened to the music collector. Streaming is the best thing that ever happened to the music lover.

If we assume the same album on vinyl or digital, from my experience, the single biggest factor is the quality of the DAC or record player, assuming the rest of the system is up to it.

Unfortunately most affordable CD players did a bad job of converting digital to analogue. And still do, as do many current DACs.

I’m of the opinion that unless you are in the know, good sound quality is more affordable for record players than DACs.

It isn’t really that LPs are fundamentally better than digital. It is just that getting digital back to analogue was more expensive/complicated than anticipated.

I also think digital arrived and took over during peak loudness wars which stuffed sound quality anyway. And we’re in some part, as I understand, made more extreme by the capability of digital to run lower frequency and more extreme waveforms since there is no needle jump issue.

I find there are massive differences between DACs and even some cd players that currently sell for $5k aren’t great. DACs which are equivalent to big name brands, where the big names retail around $8k, are very good. And there are some smaller brands doing very well and equivalent to this for $2k.

I think you’ve hit it right on the head. What I was getting at is that now that we have kind of figured out digital, and lossless streaming and fast internet are available, the listener has millions of albums available to him/her for the price of one vinyl album per month. Is it going to sound as good as an lp on a great table? No, but it’s pretty damn close.

I do a fair amount of streaming and it’s awesome to have that instant power of selection available. Many times it sounds incredible. And except for a very poor mastering job, streaming or digital disc playback is always more accurate than vinyl playback. There is still something I enjoy more about listening to a record.

I’ve always thought it was because the turntable needles’ reception is not limited to the record groove.vinyl FEELS the room????

My opinion is pretty much the opposite. I feel like at the lower end of the price range, digital sounds better. It’s definitely more accurate. But it depends entirely on what each listener values when they say something sounds good.

The devil is in the details. Both analog and digital can sound great if the engineers put their respective tools to their best use. Records make a virtue from the necessity of not brick-walling dynamics or cutting with too much treble energy (RIAA EQ is up 13.6 dB at 10 KHz vs. 1 KHz).

Excellent article Dave! Thank you.

Let’s say I’m an audiophile too and have been listening to music for about fifty years.

If we examine with historical perspective the devices that, on average, we used forty years ago, to most of us the jump to the digital reader was a great qualitative jump. In addition, most of the vinyls from the 70-80’s had a low recording quality, a rather poor pressing, and they weren’t even close to the 180 grams of recent audiophile recordings (the oil crisis had a very negative effect on the quality of the vinyl).

So, when I bought my firsts Marantz compact disc (CD60 and CD64 KI) I was amazed and parked my CEC turntable and Ortophon cell for years.

Then the vinyl almost disappeared; I managed to recover dozens of them from my friends who intended to throw them away.

During this period of time, I still changed my digital player: California Audiolabs (with vacuum tube output!), Audio Research, etc. Some of them I even changed the digital clock to improve the sound.

At a certain point I recoverered two old turntables: a Thorens with stroboscope and an AR with SME arm. I had a lot of fun changing cells: moving coil, AT OC9, Denon 103; moving magnet, Shure V15Vx and two or three different phono preamps.

The sound of the vinyl, with a good musical hardware seems to me subjectively superior, warmer, more reactive or dynamic.

But I have come to the conclusion that to hear a turntable that can really compete with a good digital player you have to spend a lot of money and many hours to adjust it correctly. I believe that laziness, if not stinginess, has beaten many of us.

Now I alternate, according to my mood, the two types of readers.

A final comment: I have noticed, and I am not the only one, that a good part of young people find it difficult to hear the difference between a correct and an excellent musical reproduction. I have the impression that low quality digital formats (read MP3) and the continued use of even worse headphones has created a new type of deafness: that of those who cannot distinguish the nuances in music reproduction.

By the way: a good magnetic tape on an old Revox also sounds damn good.

Thank you again for your article and excuse the poor quality of my English!

Luis / Brussels

I agree with all your points. Thanks!

Mr McNair,

I sincerely thank you for your brutal honesty in these matters! Having been an audiophile for most my life (50 now) I’ve witnessed most formats that have come and gone.

Vinyl along with triode vacuum amps amongst many others things, have been elevated to near mystical reverence.

All the while the digital (technophiles, myself uncluded) marched only to the latest and greatest tech available.

Decades past, the audio landscape was bountiful with a myriad of snake oil peddlers. The stories of yesteryear tradeshow booths of Mostercable are legendary amongst those in the know 😉

From someone who’s been in many facets of sound (re) and production, I very much appreciate your honesty!

The human ear is always the least accurate and most non-linear element in the signal-chain. And after 50 years, I’ve finally come to grips with the fact that – if it makes you sonically happy (regardless of price, tech-specs, or Interconnects fabricated by unicorns from iridium alloy mined from asteriods) that’s all that matters.

Oh, and the irony that thousands in studiods worldwide are spending $$$$ for DAW plugins just to apply said missing fq/amplitude/phase/distortion non-linearities to their tracks.

SO THAT THE MIX SOUNDS BETTER.

My 24/44.1 digital recordings sound analog. If I use 16/44.1 they don’t. What bit depth do you prefer?